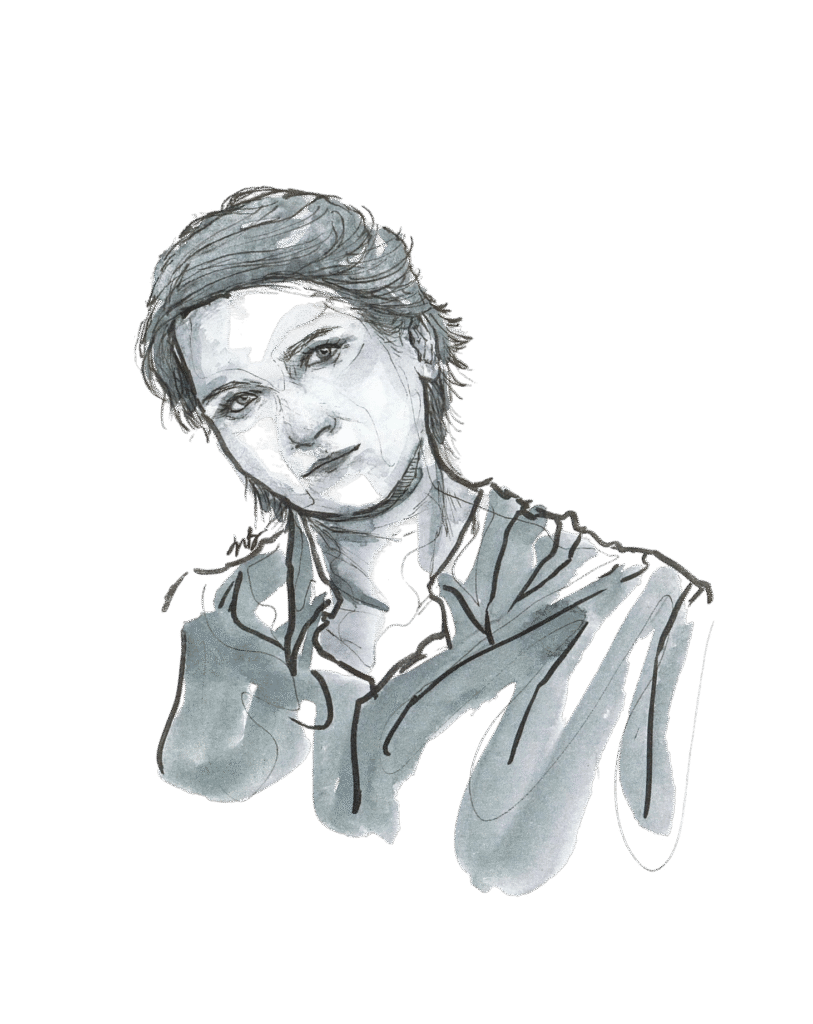

Madeleine Peyroux is an American jazz singer and songwriter who began her musical journey playing on the streets of Paris, France. She is probably on the road, or resting in Kingston, New York.

It is late spring at a café table on the cobbled center square of old Nice, dappled with the day’s first rays of warmth. I am sitting with my bandleader, teacher, and friend, Danny Fitzgerald, and his nephew Nyles. The intermittent sunshine beckons a clear blue sky over the coastal city, which will bring out the tourists, and to us, our bread and butter.

Like the uneven pavement, wrought iron tables, and rattan chairs, Danny himself is a fixture of these outdoor cafés. At times he is ritualistically stirring sugar into his espresso with a tiny spoon and laughing with neighboring patrons. At times he is standing before them, performing his own brand of Americana with his band. Dancing around these tables, he tips his bowler hat, collecting his wage, as if harvesting berries. His fingers are thick and strong like his body, but his movements delicate. For decades he has sported the same crescent of white hair cut to the shape of his scalp, which gives a contrast to his symmetrical features and caramel skin. With very few hairs on his brow, he looks slightly surprised, or perhaps perpetually ready to smile.

Nyles is blessed with those larger-than-life eyes that only seem to exist in children—light catching eyes, irises silvery blue—in such contrast to his thick, black brows and sandy hue that his beauty has an almost shocking effect. He has come from the States to spend the summer before starting college. He is gentle, relaxed for his age. Danny loves Nyles. I can see it in the way he grins whenever they speak.

The Lost Wandering Blues and Jazz Band was Danny’s midlife creation, around the time I was born on the White side of town. Today I am one of its veterans. I have now learned hundreds of songs, and played as many street corners with his washtub bass and bag of funky hats. I have covered as many highways, dozing off to the sound of Bessie Smith, squished into the rear bench of the old Mercedes with guitars and sleeping bags over my knees.

Blues and jazz are American, originally African American, and they have become my whole life since I came to France, somehow far enough away from their origins to allow me to meet someone who would teach me this music and ultimately change my life. Danny is from upstate New York; he used to live practically around the corner from my home in Brooklyn, but there, we were worlds apart. He often remarks that we would never have met had we not left. We were kept apart by our nation’s singular brand of segregation, its ubiquity in all affairs of daily life, both past and present. This beautiful music which I love so much, and its empowering, accompanying culture, were not fully available to me from within those shores.

We sip our steaming espressos and sigh in unison, swooning in the easy tempo of the south of France. Nyles and I exchange winks while Danny stirs his cup with percussive gusto. Then, Danny suddenly turns, and with a loving grin that only he can make, both genuine and coy, he sets down his coffee cup, focuses his gaze fully on Nyles, and poses this question: “Now, who are you supposed to be?”

Nyles laughs, assuming that Danny is teasing him. But Danny doesn’t crack. He only speaks more slowly, and more emphatically: “I said, who are you supposed to be?”

Nyles looks bewildered. “What?”

“Don’t you understand me when I am speaking to you? Who are you supposed to be?!”

Now Nyles thinks Danny is picking on him. He bristles. “What do you mean? I am who I am!”

“No, no, no, no, no. That is not an answer, man. ‘You are who you are’—Well, who is that?” Danny rubs his palms together gently, patiently. He smiles softly with his gaze and the coyness in his face morphs into anticipation.

Nyles seems suddenly nauseous. His back stiffens, but fails to stop him from sinking into his chair. His eyes dart around the square, seeking something or someone to distract him from this new burden, finding neither. He winces, but Danny is unfazed. “What are you asking me?”

At last, Danny replies, “Anyone can say, ‘I am who I am.’ Of course you are who you are. Everybody says that. But hear this. You can’t become who you really are until you can say who you really are. Let’s say you know something. Well, you may think you know things because you are here now, and that’s good. But where are you going? How will you know it is not the same trip you are taking over and over again? You won’t. Because you don’t really know what you know until you know this first. Because you can’t be sure of anything if you don’t know yourself.” Nyles is listening closely, his blue eyes widening with every word.

What I learned from singing with Danny’s band was much more than can be transcribed in notes and rhythms and lyrics because it is about living. The freedom he forged in France is possibly the most thoroughly realized American dream I will ever witness. Playing music in the street is the art of living in the world without being of the world. And Danny has mastered it; he is the godfather of the buskers.

The world has stopped moving now. Danny and Nyles are sitting still. They are peaceful, quiet. Their conversation has paused. They have done their work, lived a thousand lives, and have nothing more to say. They have turned their faces toward me, toward all of us. In their eyes are eternities. We have no distractions. We have no choice but to watch them. They are waiting for our answer to this one, perfectly worded question.